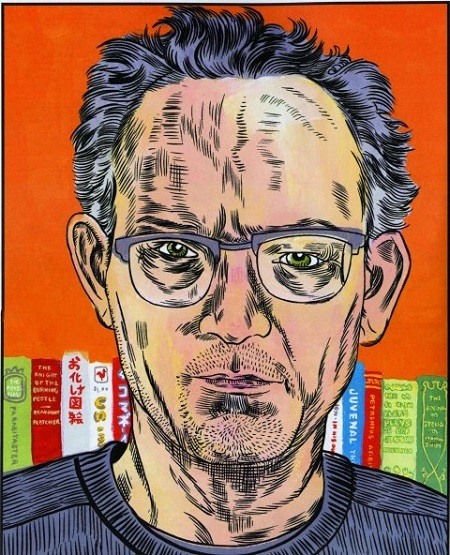

Gary PanterArticle by Mike Dixon Published in RW #11, 2005

Self Portrait © Gary Panter/Metropolis Magazine Gary Panter's answering machine sounds like a dilapidated robot. The creaky mechanical monotone is a perfectly appropriate voice for notifying callers that the artist is unable to answer at the phone. Since the late '70s, Panter has spread his inimitable alternate-universe visions across the world, in the form of countless books, comics, art exhibitions and installations, performances, animated cartoons, record albums, toys, housewares, and on and on into infinity. His work across so many mediums is an inspiring and true testament to the power of imagination. He's a really nice guy, too!

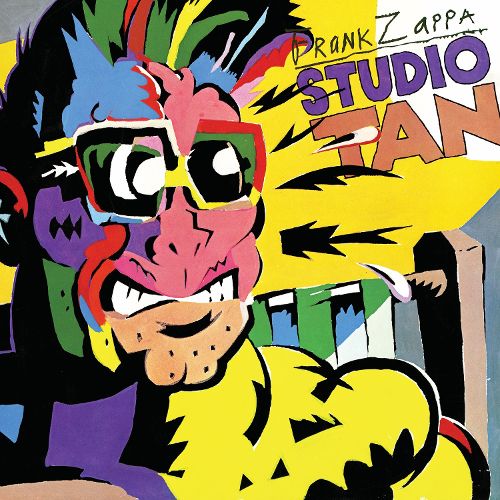

Gary was born in Texas, and in his first eight years, his family bounced from one mid-western city to another before settling in Sulphur Springs, TX. After he graduated from the painting program at East Texas State in 1974, Panter says, "I got out of college and I couldn't get any work in Austin or Dallas doing illustration work, so I took what little money I had and went to Los Angeles. I met a guy who let me sleep on his couch and I became a commercial illustrator." He found plenty of work in L.A., and shortly after arriving, he designed a trio of Frank Zappa album covers.

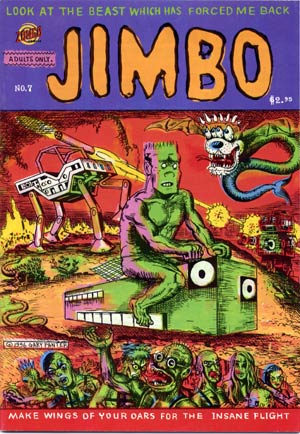

Panter the fan was later chagrined to learn the records had been released by the label against Zappa's wishes. Around this time, punk "happened" and Gary happened upon it. "I remember going into a hip record store and saying 'Gee, what are the good records now?' and the guy going 'Well, you know, Todd Rundgren, and Sparks. So I was listening to that stuff and kind of enjoying it, but wondering 'what else is there?' Then I saw Slash magazine on the newsstand, and saying 'Oh,wow. This looks interesting'." This was 1977, and Panter became involved in the burgeoning punk scene and began contributing comics to Slash. These strips were drawn in an unprecedentedly raw and ratty style that more or less set the template for "punk" graphics that have endured to this day. They featured the adventures of Panter's everyman hero Jimbo, a kind of half-punk, half-caveman (and part-time grad student), who wanders around a not-too-distant future suburban wasteland. Around this time, Panter became acquainted with Paul Rubens, aka Pee Wee Herman. "He noticed some of my fliers around town and he got ahold of me somehow." Soon they were collaborating on the stage production of The Pee-Wee Herman. When Pee Wee made the jump to the big time, Gary was brought along to design the sets, characters, and even the spun-off product lines for the Daytime Emmy Award winning Pee-wee's Playhouse. "We were nominated five times and won three times. It's a big deal. Everyone's in suits, and it goes on forever. Florence Henderson—the mom from The Brady Bunch—sat at our table, but I was about five years too old to really appreciate it." In the ensuing years, Panter continued with commercial work, while making paintings and publishing a steady stream of hallucinatatory comics, notably in Art Spiegelman's Raw anthologies, in the Japanese reggae (yes, Japanese reggae) magazine Riddim, and in the deluxe, folio-sized book Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise. Panter's loosely serialized stories are set in the city of DalTokyo. "I look at it as being kind of a theater. Like, the character Henry Webb plays a lot of different bad guys. Sometimes he's the same bad guy, but sometimes he's like a bad guy who keeps dying and keeps being reincarnated with slightly different bad personalities. Sometimes he's a little bit better, sometimes he's a little bit worse. But the characters are basically playing parts. I have a hard time killing characters off, and having bad things happen to them. So a lot of the story is really about the place they're in, DalTokyo. There's a theme in my comics which is that the authoritative powers try to take care of you, and there are all these robotic denizens that are trying to enforce the rules, so it's always very oppressive.

From 1995 to 1997, Matt Groening's undergroundist Zongo Comics imprint began publishing Jimbo on a quarterly schedule. The first issue was rendered with an absurd crudeness unprecedented in "professional" comics, even considering Panter's reputation as the master of controlled chaos. With each issue, the rendering became incrementally cleaner, the three distinct storylines (one involving Jimbo's arrest for loitering and imprisonment in a luxury spa/prison, another about two hillbillies and their city slicker cousin's misadventures slaughtering chickens, and a third following an FBI investigation of a mysterious bus accident) slowly converge, and the panels become progressively more detailed and intricate. By the end of the series' seven issue run, Panter was using Dante's Inferno as a narrative template, and employing 19th-century-style crosshatching. But the series ended with stories apparently unresolved. Then, six years later, Panter continued Jimbo's adventure with the giant-sized Jimbo in Purgatory, the natural next step in adapting Dante to DalTokyo. "This Purgatory strip is actually a continuation of it. It's an extension of that idea of tightening up more and more each issue. But I'm not sure I'm going to continue to tighten up. It's funny when people look at it and talk about how scratchy and crude it is, and I think it's not." One thing that Panter does agree with readers of Purgatory, though, is the inscrutable density of the book. It's an impossibly concieved adaptation of an arcane source, with each pages references, from Virgil to Westworld to the Old Testament to "Two Virgins" footnoted. Panter says "It's hard in every way. I don't mind that it's challenging, but I'm not going to become some sort of literary critic comic artist. I don't have it in me." Panter is unsure whether he'll bother tying up the other loose narrative ends. He says he probably could come up with a satisfactory conclusion, but he's got a lot of other work that he's interested in for the time being, and in his mind he keeps his work between mediums separate. For instance, "painting tends to be separate from comics. They're both personal, but they're different. When I was really young, I thought 'Oh, I'll do comics, and then I'll do paintings of them.' But when I started doing that, the paintings looked bad to me, so I decided just to keep them separate. Comics are hard work. The whole enterprise is very time-intensive. The weird thing about Zongo 1# was how hard it was to even do crappy work." For the past half-decade, Panter has been active developing and performing electric light shows. He explains: "A few years ago, I built a little theater in my studio. It's a solid black room, with a screen about three-by-four feet. I started doing little light shows there, but I could only do them for about eight or maybe ten people at most. I did a lot of those shows, then that whole thing ended. About a year later, this gallery in Brooklyn, Pierogi, the owner Joe Amrhein invited me to do a light show in his performance space. So I set up there and did about fifty shows in a month. Through that I met Joshua White, who did a lot of big light shows at the Fillmore East in the '60s. So we started getting more and more equipment, and involving Josh to make a bigger light show. Then last summer, we did a full-size light show—I don't know how big, about twelve-by-thirty or something at the Anthology Film Archives. And this year we're doing a couple of other light shows, and one of them's kind of big. Then we're thinking of trying to make what do what we do smaller. The smaller we make it, the more sensitive articulated kinds of things you can do, and the bigger it gets, the more people you need. It's a hand light show, it's not a computerized light show, so we have to be back there bending things. It's free form, but somewhat structured. There are a number of things you can do, and you make the tools you need to do them. We've done them with pre-recorded music by a friend of mine who made a tape collage for us, and we've also done them with live music. I played with Bardo Pond in Philadelphia, and we played with Yo La Tengo and Alan Licht in New York. Alan played quite a few shows with us. They look like '60s light shows. We use all these overhead projectors that are left over from Josh's shows. So that globby kind of thing like—you know the cover of "In A Gadda-Da-Vida"? That was a photo of Josh's light show. And then the stuff I was doing was using stencils and bouncing light in back of the screen—aiming light away from the screen and then bouncing it back, bouncing it through things, which is more like a beatnik light show. The thing that Josh liked about my light show was that it was just a hand-done one. There's a million people asking him about light shows, but 99.9% of them are computer light shows, which are cool, but it's a different thing.What we're doing is using really bright light sources that are really small, motorized color wheels that we hand cut and build, mobiles that are shiny—anything shiny, anything crystalline. You can make big mylar mirrors and tap the backs and control the image. So there's a lot of ways you can kind of put your hands on the light. We have it set up where if I just move my finger, the whole image jumps around. Josh has been a director for a long time, and he's super organized, so I'm happy just to see what happens." Two years ago, Panter started his website (found, straightforwardly enough, at www.garypanter.com) and began offering custom-made drawings for $100 apiece to the first one hundred customers. After the first hundred were spoken for, the price increased to $125, and so for each hundred sales, there is to be a $25 price hike. Presently priced at $175 a pop for a 6"x8" black ink and wash drawing, the drawings are a product of Panter's free-associating upon one to three words chosen by the customer. Gary says, "I do drawings that are two and three times bigger than this that I show in galleries that I sell for two or three thousand dollars. People have said to me 'Oh I like your work, but I can't really afford it... maybe someday'. And I just thought, well I can make something that's cheap, but I didn't want to be doing drawings for a hundred dollars a piece for the rest of my life, so if the price slowly goes up. Maybe that's the cheesy part of it, I don't know. I like reaching another hundred drawings and saying 'Ah, another twenty-five dollars'. Then the people who bought them the first time around say 'now I've gotten a deal'. I don't know how long I can do it. Maybe I can do it forever, maybe another couple of years. But in the meantime, a couple hundred people will get my drawings. It's really hard with pricing. It's hard to explain to my twenty year old fans who like my work how expensive the life of an adult is. But really, it's been great. I've always supported myself doing commercial art, and when you're a freelance, the phone rings sometimes, and sometimes it doesn't. And this has been oddly consistent. I sell a drawing about every three days. I'm always working on a few, and I haven't gotten tired of it. If I felt like I was doing bad drawings I would stop, or if I got tired of it, but so far it's been fun." "I work a lot. Seven days a week, all day long, all night long, with a million interruptions. I go to teach on Mondays, family stuff, food-buying, cat-boxing, lawn raking. There's something about my brain that loves painting and drawing. Read more interviews with Comics Artists:Peter Bagge

|

|---|

|

|